Our website uses cookies so we can analyse our site usage and give you the best experience. Click "Accept" if you’re happy with this, or click "More" for information about cookies on our site, how to opt out, and how to disable cookies altogether.

We respect your Do Not Track preference.

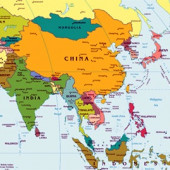

In our inter-connected world, legal advisers to businesses that operate online are increasingly expected to know or be able to find out something about other countries’ privacy laws. Asia is one of the world’s most significant economic regions and it is important to understand how the data protection and privacy environments of Asian countries work.

While Asia is a key region for New Zealand companies, up to now it has not been easy to get up-to-date and reliable information about the privacy laws in countries as disparate as Vietnam and Indonesia. How, for example, do we differentiate between the regulatory roles of South Korea’s soup of agency acronyms like PIPC, MOSPA, KISA, PIDMC or KCC? How do we find out if there are controls on telemarketing in Singapore or on ID card numbers in Hong Kong or Japan (for your information, controls exist for all of them)? Clearly, a more authoritative source than Wikipedia is needed.

Help is at hand in Professor Graham Greenleaf’s newly published book Asian Data Privacy Laws: Trade and Human Rights Perspectives. The 579 page book explores information privacy in 26 Asian jurisdictions, of which nine are covered in depth. Up to now, the standard texts on privacy law have not covered the Asian region in any depth and this useful book fills a beckoning gap.

As is appropriate for a book covering a region where privacy law is relatively new (other than in Hong Kong where the law was adopted shortly after New Zealand’s), Prof Greenleaf’s work places each jurisdictions law within a social, cultural, legal and economic context. Thus we read of how the data privacy laws fit within Hong Kong’s common law system transferring to become part of the law of a special administrative region of China. We also find out how privacy laws were viewed as a protection from state abuse in South Korea, a civil society that emerged in the 1990s from a military-dominated regime with a strong state surveillance apparatus.

The heart of the book uses a series of standardised categories to aid descriptions and comparisons across the economies featured. This does not result in a boring, dry-as-dust tome. I found the book very readable, although I admittedly fall within a target audience of people interested in the minutiae of privacy law and policy. Prof Greenleaf deals with the finer details of many laws and doesn’t hold back on his opinion of strengths and weaknesses. A clue appears in the chapter headings. These range from the positive (South Korea - the most innovative law), the middling (Singapore - uncertain scope, strong powers) to the somewhat damning (Japan – the illusion of protection). Prof Greenleaf doesn’t pull his punches and that makes for a good read.

Back